MEMO RE CORPORATE GOVERNANCE

You’ve asked us to prepare a memo covering some key corporate governance issues pertaining to startup companies. “Governance” is the term we’ll use to describe the system of principles and processes by which a corporation is managed, and covers the relationship between the Board of Directors, shareholders, management, and other stakeholders. The goal of a corporate governance system is to promote stability, predictability, and long-term shareholder growth. This memo briefly outlines key concepts and considerations in developing an effective corporate governance structure.

1. Shareholder “exposure” vs director “exposure” in terms of liability to the individual; fiduciary duties.

Many startup teams worry about their level of exposure to liability by joining a startup in any capacity. In a corporation, both shareholders and directors/officers are protected from liability by the nature of the corporate form, with some exceptions outlined below (note that this is not exhaustive, but these are the general considerations for the purpose of having a meaningful discussion).

Shareholders

In general, shareholders are not personally responsible for the liabilities and debts of a corporation; their liability is limited to the value of their investment (i.e. the shareholdings) in the company. This means that a corporation may not force shareholders to pay for corporate income taxes, to pay a creditor of the company, or to pay a judgment against the company.

However, shareholders can in theory become liable for corporate obligations in specific situations such as if a shareholder expressly agrees to personally guarantee a loan to the corporation. A court could also find the shareholders personally liable if the shareholders failed to follow corporate formalities (such as keeping separate books and accounts for the corporation), consented to an illegal distribution, or violated law which expressly allows for shareholder liability (such as a violation of securities laws).

Directors

While directors are also protected by the corporation’s limited liability shield or “veil,” directors have nonwaivable fiduciary duties that, if violated, could expose them to liability. First, directors have a duty of loyalty, which requires them to put the interests of the company and its shareholders over themselves. This includes offering outside opportunities to the company first before being able to take it for themselves. Second, directors have a duty of care, which requires directors to make decisions based on adequate information, and a good faith belief that their decisions are in the best interest of the company and its shareholders. Violations of either of these duties can subject directors to personal liability.

In general, these duties require directors to make decisions based on what they reasonably believe is in the best interest of the company and the shareholders. While it is understood and expected that directors will use their own personal experiences, expertise, and judgment in making decisions, this accepted reality does not allow a director to make a decision for personal reasons if that decision puts the best interest of the director ahead of those of the corporation—and specifically, its common stockholders. Directors’ decisions must reflect the best interests of the company or the shareholders.

And don’t forget…

Prior to the injection of capital, the far greater “exposure” or liability is the risk that the active team members, regardless their role, lose time they invest in a venture that struggles to get off the ground. Where teams are confused about the direction of the company, the relative priorities, and leadership, it can be an excruciating process to unwind the progress to date and shut everything down. For some, it’s a total loss to many of all the time they’ve invested in the venture.

2. The different roles between shareholders and directors regarding management of the company.

Shareholders and directors have two completely different roles in terms of managing a company.

Shareholders: As owners of the shares of the corporation’s capital stock, shareholders have two key rights: (1) the right to the economic benefits that derive from the value of the shares, and (2) the right to vote to elect the directors and vote on fundamental decisions affecting the company as a whole (such as dissolution, major sales of assets, removal of directors, mergers/acquisitions, etc.). Director votes usually take place at the annual shareholder meeting unless a shareholder calls a special meeting. Shareholder votes are typically tied to the number of shares they hold, in that each share receives one vote on any issue up for a vote. In some situations, special classes of shares can be created such that the voting rights of those shares outstrips the rights of another class by as much as 10:1. E.g. Google’s Class B shares, which do not vote in public and each get 10 votes.

Directors: Responsible for managing the corporation: issuing shares, authorizing corporate actions, appointing CEO. Once the board of directors is established, however, the directors take on management responsibility and are required to manage the company in a way that reflects the best interests of the shareholders. Directors typically get only one (1) vote on any matter coming before the board. That is, even if a director is also a shareholder, the number of shares that director holds is irrelevant in the context of a vote of the board of directors. The safeguard for shareholders is that they have the right to replace directors if the shareholders feel the directors are not voting in the shareholders’ best interest.

3. Equity Splits / allocations of shares in startups.

Many startup founders are surprised to find out that the biggest struggles over shareholdings often are about control and not about economics, meaning that it’s the second type of shareholder right we mentioned earlier—the voting right—that often stalls decisions. Every company is different and there’s no “right” way to split equity between a founding team; the split must take into account the need for fairness, efficient decision making, and good governance.

Any split should also keep in mind that few startup teams have more than a majority of shares all combined following a few rounds of venture funding, and Series A investors often take 10-15% of equity and end all notions of any one controlling shareholder fairly early in a company lifecycle. See the super-cool graphics on this by Capshare.

It might be helpful to think of options in terms of models:

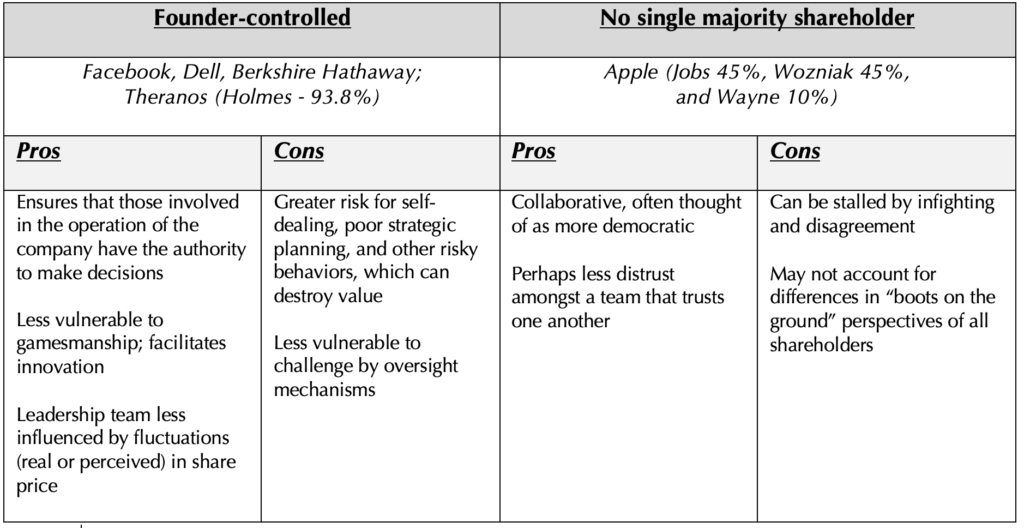

CEO/Founder-led: Similar to Facebook (Mark Zuckerberg) or Dell (Michael Dell), these companies’ founders have had control by controlling more than 50% of the shares for many years of the companies’ existence. In a young company with no revenue and no significant investor, the primary concern is ensuring that the leadership of the company (which sometimes is the entire company) have some freedom to make decisions without undue concern about those decisions being second-guessed. Otherwise, shareholders who are not as keenly aware of the dynamics of the company can stand in the way of the company taking necessary steps forward. People in this camp often subscribe to the view that the majority of the shares should rest with the one person who shoulders primary responsibility to move the company forward, to give that founder at least some breathing room. As other team members prove more indispensable to the business, they can either negotiate for a greater share of the pie, and a worthy leader could be trusted to either recognize those contributions or otherwise create incentives for that individual to stay on board.

There’s no “I” in team: One company that survived without a single controlling shareholder from its earliest days is Apple. While Apple was technically a partnership at that time, the corporate concepts can be disregarded for purposes of illustrating this point: Jobs: 45%/ Wozniak: 45% / Wayne: 10%.[1] The group could only spend company funds greater than $100 if both Jobs and Wozniak were present to vote (i.e. supermajority quorum of 75%), though a 51% vote (i.e. either of Jobs/Wozniak with Wayne) could carry the day. The “school” of thought that underpins this governance model is that a young company can thrive and be successful without having any single founder/CEO retain complete control over the board; however, it typically often entails a fair degree of synchronicity between any founders who do together have more than 50%.

The primary justification for consolidation of decision-making authority in one person is that in the early days of a company, opportunities may be few and far between. If a complex mix of shareholders must approve every action the company takes (or threatens the CEO with removal at the slightest hint at disapproval), the opportunities will pass before the company can take advantage of them.

While this may be often unsettling to minority shareholders, it is important for them to remember that they possess leverage as well: primarily, their leverage is the right to walk away from the company. Minority shareholders in an early-stage company are usually granted shares in exchange for their affiliation with and service to the company. Without those services, the company would not be able to operate, and might face reputational harm from the exits of too many early co-founders. Minority shareholders in an early-stage company have direct access to the majority shareholder and are usually able to participate in decisions to the extent they desire.

Two final points for minority shareholders to remember: First, an incompetent majority shareholder will drive a company into the ground. It is better to get out early and start a competing venture with trusted management. Second, if minority shareholders do not trust the controlling shareholder, the must either negotiate for minority protections (at the elevated cost to the company) or they should not participate in the venture. At some point, a leader must emerge and must be trusted to make good decisions for the company. If a minority shareholder does not trust this leader, the minority shareholder may be better off not participating in the venture than attempting to handcuff the leader.

4. Common pitfalls like deadlock, stonewalling, etc.

To put it simply, early-stage companies that lack an effective governance system for their specific combination of founders do not survive. There are likely several allocations of shares + contractual arrangements that could work, and the important part is to pick one. At some point, the inability of those responsible for making the company work to make decisions makes it impossible to do a job effectively and leads to frustration and a breakdown. Common pitfalls include:

(i) Deadlock. Companies at any stage can face decisions that determine whether the company can continue as a going concern. If the company cannot act in these situations due to shareholder disagreement, i.e. because it can’t reach a quorum to take a vote, the company has become deadlocked and the operations of the company come to a standstill. If the issue cannot be resolved, the company must dissolve. Deadlock often occurs because the founders avoided making difficult decisions early on regarding dispute resolution and failed to install a mechanism for resolving disputes. In these situations, a promising company with a viable business model crashes before it even gets off the ground. This is always a disappointing outcome, and is a frustrating waste of time for those who participated up to that point.

(ii) Stonewalling. Stress and disagreement can bring out the worst in people. Rather than come to the table to address the challenges facing the company, some people instead decide to stonewall and refuse to engage in meaningful dialogue. If this person has the share power to prevent the company’s continued operations, the company essentially stalls and no further progress can be made. Like deadlock, the company is stuck and likely must dissolve.

(iii) Third-party signaling. Third parties, such as investors, vendors, or customers, want to know that there is a person in the company who has the authority to speak on behalf of the company. To these outside parties, there is no point entering a negotiation unless they can trust that what they bargain for will be honored. Similarly, a person trying to negotiation on behalf of the company has little chance for success if they do not know whether they can honor the representations they make, or are unable to make commitments at all due to the handcuffs the other shareholders have placed on them. In a negotiation, this person will look unprepared or lacking in confidence which will lead an investor to question whether their money would go to good use by the company.

(iv) Leadership. Starting and working at a company are inherently collaborative efforts. Everyone involved must work together towards a common goal. However, collaboration and group decision making are independent of the issue of leadership. Ultimately, a team with a way to arrive definitively on what the vision of the company is, what the goals are, and what actions will be taken in order to get there. The failure of a team or company to establish a clear leadership structure leads to chaos and confusion. Even if different people have authority over different aspects of the company, these divisions of authority must be clear in order for the company to act decisively and move forward.

5. Possible ways to structure around the extremes above.

A few options that can work for teams seeking resolution that lands somewhere between the generic models described above:

- a) Imposing supermajority quorum or voting rights for certain decisions (via the articles of incorporation or bylaws)

- b) Adopting restrictive signature authority policies

- c) De-coupling economic rights from the voting rights. In other words, if certain shareholders are more concerned with the economics of the equity split than the decisionmaking authority, consider granting these shareholders more shares in exchange for their assignment of voting rights to another shareholder via a proxy agreement.

- d) Shareholders’ agreement. Another alternative is for shareholders to enter an agreement which acts as a governing document for how the shareholders act as managers of the company. A shareholders agreement can be customized to specify if certain decisions require approval of the shareholders, and if so at what percentage (majority, supermajority, etc.). In this way, the shareholders attempt to strike a balance between the need for efficient decision making, and the desire to create reasonable limits on the CEO’s authority.

Whatever direction you take when it concerns the equity split, make sure you’ve got good legal counsel leading the way. #goodlegalisgoodbusiness

[1] Apple Computer Company, Partnership Agreement (Apr. 1, 1976), https://downloads.reactivemicro.com/Apple%20II%20Items/Documentation/Apple%20Info/Apple%20PartnerShip%20Agreement.pdf.